Prison memoirs are an immense literary & political genre written by political prisoners from Stalin’s gulag, China, Turkey, Iran, Egypt, Guantanamo, Blacks in the US, Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Ireland, Kashmir, India, Nazi Germany, Spain, Italy, Argentina, Burma, & many other countries. Increasingly, women, especially Iranian & Syrian women, are writing of their experiences as political prisoners subject to torture & sexual assault (though as we know from CIA, Iranian & Kashmiri prisoners, men & boys are also subject to sexual torture). It is a gruesome genre but no other gives deeper insight into the character of governments that imprison dissenters. It’s impossible to rank savagery, but the Syrian gulag ranks with the Stalinist, Iranian, & CIA prisons as among the most barbaric in human history.

Perish the thought that such gulags are a non-western phenomenon. They are deeply rooted in the legacy of colonialism where most colonized were not imprisoned but slaughtered or enslaved. Testifying to that are Long Kesh, the British prison in Northern Ireland where Irish republicans were housed with murderers & rapists, Guantanamo, CIA rendition prisons like Abu Ghraib in Iraq & Bagram in Afghanistan, the US concentration camps for refugees, Manus Island & Nauru prison for refugees in Australia.

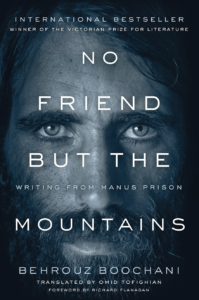

“No Friend But the Mountains” by Iranian-Kurdish journalist & human rights activist Behrouz Boochani is about his experience in Manus Island, a penitentiary for male refugees seeking asylum in Australia. All of the refugees have gone through harrowing experiences fleeing war & persecution but are imprisoned rather than processed for asylum. The Australian government apparently outsources its refugee prisons to profiteers in the same way the US does its prisons & refugee concentration camps. These companies must dredge the sewers looking for psychopaths & sadists to staff them & their is no accountability for their cruelties. Behrouz also describes the racist way the prison employs Manusians for low-level undesirable jobs like washing down the toilets.

Bezrouz’s poetic style & sensibilities contrast with the graphic rawness of what he describes. In its rawness, the book is reminiscent of “My Testimony”, a 1969 memoir written by Anatoly Marchenko about the Soviet gulag. Most prison memoirs are written by intellectuals but Anatoly was a 19-year-old unschooled, apolitical laborer arrested in a drunken brawl. He was politicized in prison by political prisoners & wrote three prison memoirs. Solzhenitsyn, renowned for his gulag memoirs, described Marchenko as the true historian of the camps of the 1960s. He died in a prison hospital in 1986. Anatoly’s book is reminiscent of Bezrouz’s in their descriptions of how humiliation, especially the use of machismo, is systematically & sadistically employed by prison officials. Everything, especially eating, showering, & going to the toilet, is used to insult dignity & the sense of manhood to break down social cohesiveness among the refugees & create a sense of solitary confinement.

At times, Bezrouz seems almost cranky toward other prisoners but the book was written whilst he was in prison. He refused to participate in the sadistic conflict & competition for food set up by the guards & was hungry most of the time. In that way, the book is also reminiscent of “The House of the Dead”, the 1860 semi-autobiographical prison novel by Dostoevsky about life in a tsarist Siberian prison camp. He describes the cruelty of the guards but also the antisocial, criminal behavior among prisoners–although Russia did not separate political prisoners from common criminals.

The 2019 edition of this book has an introduction by Australian novelist Richard Flanagan who claims Bezrouz as “a great Australian writer”. Since Bezrouz never set foot in Australia, was imprisoned by Australia in barbaric circumstances, & does not intend to apply for asylum in Australia because of that mistreatment, it is presumptuous of Flanagan to make that claim. Behrouz was an Iranian-Kurdish writer which is the reason he fled for asylum.